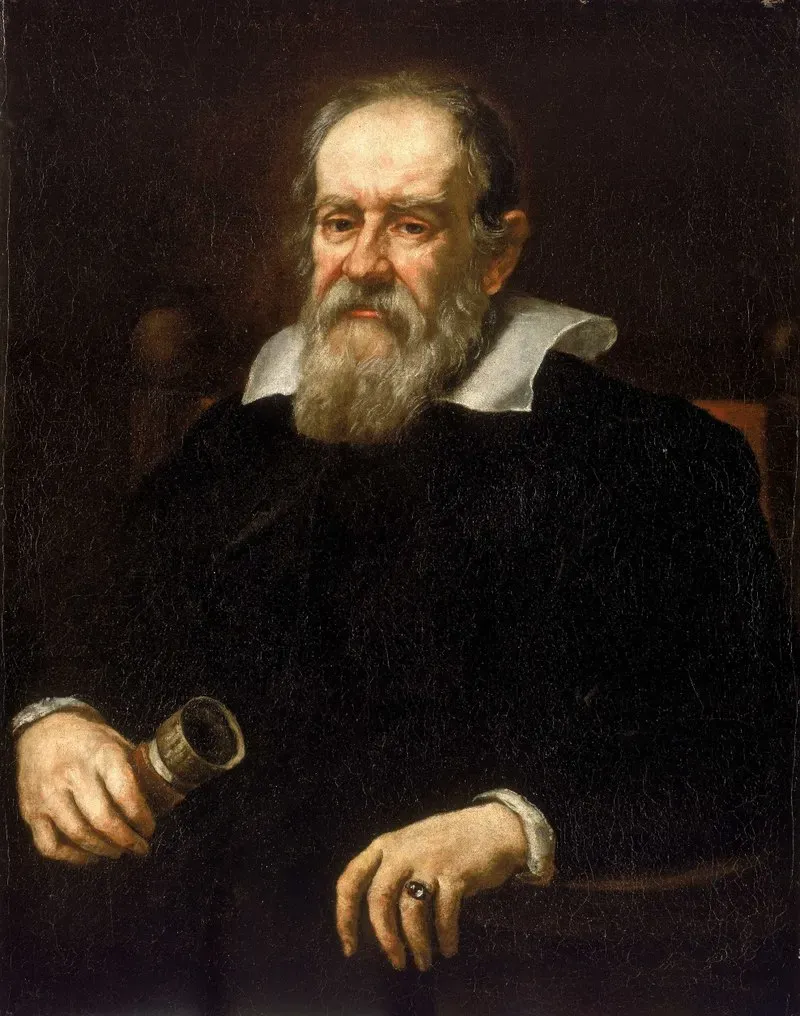

Full Name: Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei

Date and Place of Birth: February 15, 1564, Pisa, Duchy of Florence (now Italy)

Family Background: Galileo Galilei was born into a relatively affluent family. His father, Vincenzo Galilei, was a renowned lutenist and music theorist, who significantly influenced the field of music through his studies on acoustics and the relationship between pitch and string tension. His mother, Giulia Ammannati, came from a noble family. Galileo was the eldest of six siblings, with his brothers and sisters experiencing various levels of success and hardship.

Early Life and Education: Galileo’s early education took place at the Camaldolese Monastery at Vallombrosa, near Florence. Recognizing his intellectual potential, his father enrolled him at the University of Pisa in 1581 to study medicine, which was a prestigious field at the time. However, Galileo’s interests soon diverged towards mathematics and natural philosophy, much to his father’s initial disappointment. He left the university without a degree in 1585, but his time there was instrumental in shaping his future scientific endeavors.

Nationality: Galileo was born and spent the majority of his life in what is now Italy. During his lifetime, the region was fragmented into various states and duchies. As a native of the Duchy of Florence, Galileo was considered a Florentine by nationality.

Career: Galileo's career can be divided into several phases, each marked by significant scientific achievements and contributions. After leaving the University of Pisa, he began teaching mathematics in Florence and Siena. In 1589, he secured a position as the chair of mathematics at the University of Pisa, where he started to challenge the Aristotelian physics that dominated academia. His experiments on motion, particularly the famous (though possibly apocryphal) experiment of dropping spheres from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, began to earn him recognition.

In 1592, Galileo moved to the University of Padua, where he taught geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610. These years were particularly fruitful for his scientific research. He improved the design of the telescope, which had been invented in the Netherlands, and began a series of astronomical observations that would revolutionize the understanding of the cosmos. His discoveries, published in "Sidereus Nuncius" (Starry Messenger) in 1610, included the moons of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, sunspots, and the rough, mountainous surface of the Moon.

His work brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church, which upheld the geocentric model of the universe. Despite this, Galileo was appointed as the chief mathematician and philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany. His later works, such as "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems" (1632), openly supported the heliocentric theory proposed by Copernicus, leading to his infamous trial and house arrest.

Personal Life: Galileo never married, but he had a long-term relationship with Marina Gamba, with whom he had three children: Virginia, Livia, and Vincenzo. Given the constraints of his time and the stigma attached to illegitimacy, his daughters were placed in convents, with Virginia becoming Sister Maria Celeste, who maintained a close and affectionate correspondence with her father until her death.

Challenges and Obstacles: Galileo’s support for the heliocentric model of the universe brought him into direct conflict with the Catholic Church, which held the Ptolemaic (geocentric) model as doctrine. In 1616, the Church formally declared heliocentrism heretical, and Galileo was warned to abandon his support for it. His publication of the "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems" in 1632 was seen as a direct challenge to this decree, leading to his trial by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. He was found "vehemently suspect of heresy," forced to recant his views, and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. Despite these restrictions, he continued to work and write, producing significant scientific texts that were published posthumously.

Major Accomplishments: Galileo’s contributions to science are vast and varied. His improvements to the telescope and subsequent astronomical observations provided solid evidence for the heliocentric model of the solar system. His work in mechanics, particularly his studies on motion and the laws of inertia, laid the groundwork for Newtonian physics. He is also credited with the development of the scientific method, emphasizing experimentation and observation over philosophical speculation.

Impact and Legacy: Galileo’s work fundamentally changed the scientific landscape, challenging centuries-old beliefs and setting the stage for modern astronomy and physics. His insistence on empirical evidence and systematic experimentation became the cornerstone of the scientific method. Despite his conflicts with the Church, his legacy endured, influencing generations of scientists and thinkers. His work paved the way for future astronomers, including Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, and his methods are still at the heart of scientific inquiry today.

Quotes and Anecdotes: Galileo is often remembered for his wit and sharp intellect. One of his most famous quotes, “E pur si muove” (And yet it moves), supposedly uttered after his recantation, underscores his unyielding belief in the heliocentric theory despite his public submission to the Church. Though its authenticity is debated, it encapsulates his spirit of inquiry and defiance.

Later Life and Death: In the final years of his life, Galileo continued his scientific work despite being under house arrest. He wrote "Two New Sciences," which summarized much of his earlier work in physics, particularly on the strength of materials and the motion of objects. This book was smuggled out of Italy and published in the Netherlands in 1638. By this time, Galileo had become blind, possibly due to cataracts and glaucoma, but he continued to dictate his ideas to students and visitors. Galileo Galilei died on January 8, 1642, in Arcetri, near Florence. His contributions to science were eventually recognized by the Church, and in 1992, Pope John Paul II formally acknowledged the errors made by the Church in its treatment of Galileo. His legacy endures as one of the founding figures of modern science.

Comments

Post a Comment